Written by Dr Ella Henry, Associate Professor and Director of Māori Advancement, Auckland University of Technology School of Business, Economics and Law; and Associate Research Fellow, Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation.

Kia ora, greetings, I am a Māori/Indigenous woman from New Zealand, and an Associate Professor in Entrepreneurship in the Faculty of Business, Economics & Law, at Auckland University of Technology. Over the last thirty years my research has focused on Māori issues, with a Master of Philosophy in Management & Employment Relations, where my thesis explored Māori women in management and leadership. My PhD research was on Māori entrepreneurship in screen production, and in recent years I have conducted research on Māori careers, leadership, commmunity development and housing; Māori and Indigenous networking, and more recently Māori and Indigenous finance and investment. I am currently teaching entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship on the Bachelor of Business Studies.

Respecting Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Alongside my teaching and research, I am also the Director of Māori Advancement in the Business School. This role enables me to develop programmes to enhance the success of Māori students in, and support for Māori staff across, Business. This role has come about, in part, because AUT has specific goals and priorities that articulate their relationship with, and commitment to, Māori, as partners in Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi), the founding documents of New Zealand, signed on February 6th, 1840; after which this country became a British colony.

AUT Strategic Directions to 2025, Theme Three, Respecting Te Tiriti o Waitangi

“We will partner with Māori to advance Mātauranga Māori and te reo (Māori language) and achieve the benefits a university can provide with and for Māori”

mātauranga Māori and social innovation

In my view, my professional roles, teaching mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and advocating for and with Māori, alongside this University’s stance on Te Tiriti, are examples of ‘social innovation’. I draw on the work of Pue, Vandergeest & Breznitz [1], who note that there is not yet a comprehensive definition of social innovation, nor a unified theory. However, they offer their definition, as, “a process encompassing the emergence and adoption of socially creative strategies, which reconfigure social relations in order to actualize a given social goal” (2015, p.1). I argue that, acknowledging Te Tiriti o Waitangi in strategic documents, incorporating mātauranga into the curriculum, and employing Māori scholars as experts and advocates for Māori knowledge and advancement, are examples of a particular form of social innovation.

This type of social innovation is rooted in the specific historical context of New Zealand. The Māori language name for the Treaty of Waitangi is purposeful, because in that version Māori did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown. Our very wise chiefs of the past espoused a partnership model, whereby Queen Victoria would govern her people in this country, and Māori would retain rangatiratanga (leadership) over their lands and people. Unfortunately, an English version, written some months after February 6th, 1840, became the ‘official’ document, through which the first British, then Colonial, government enacted and enforced a regime, which oversaw the eventual loss of Māori lands (the economic foundation of Māori society), sovereignty, culture, and language.

Māori resilience

By the turn of the 20th Century, it was assumed in many quarters that Māori would die out (Salesa, 2001) [2], but we proved more resilient. After WWII, many Māori moved to cities, in search of work and improved lives (Hills, 2012) [3]. This resulted in what has come to be known as the Māori Renaissance (Walker, 1990), involving Māori protest and activism, that led eventually to the creation of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975. The Tribunal website states that:

By establishing the Waitangi Tribunal, Parliament provided a legal process by which Māori Treaty claims could be investigated. Tribunal inquiries contribute to the resolution of Treaty claims and to the reconciliation of outstanding issues between Māori and the Crown (Waitangi Tribunal, nd) [4].

Since 1985, Māori have lodged claims about multiple historical and contemporary grievances and egregious acts of the Crown, resulting in loss of life, lands and mana. On the 40th anniversary of the Tribunal, the Tribunal acknowledged it had:

- Registered 2501 claims

- Fully or partly reported on 1028 claims

- Issued 123 final reports

- Issued district reports covering 79% of New Zealand’s land area

By 2018, $2.2 billion had been allocated to reparations for tribes, a tiny fraction of what was lost by Māori, and a miniscule proportion of New Zealand’s GDP. However, the impacts of these settlements for tribes include seed funding for economic, social and cultural development, with the Māori economy estimated at over $50 billion (MFAT, 2018) [5]. More importantly, successive governments have accepted responsibility for these grievances, and enacted legislation and regulations to address past inequities. This has led to the creation and funding of a series of social innovations, underpinned by Māori advocacy and activism, including:

- Creation of the Māori education sector, involving immersion in Te Reo from early childcare to tertiary studies

- The setting up of Māori health initiatives, Hauora (Māori health) by, with a for Māori, predicated on Māori culture and values. In the 2021 Budget the current government will set up a Māori Health Funding Authority, a relatively independent body to address appalling Māori health statistics

- Māori involvement across the legal engaged, informed by a philosophy of restorative justice

- Māori business education and associated programmes and networks, to support tribal and urban Māori business development

Māori activism

Thus, my role, and those of Māori in other tertiary institutions around the country, further contributes to the emergence and adoption of creative strategies, which reconfigure social relations between Māori and non-Māori. Taken together, we are actualizing social goals around addressing Māori grievances from the past; whilst contributing to strategies that will ameliorate the current state of Māori impoverishment; and developing opportunities for Māori to better contribute to an enhanced future for all New Zealanders.

We, and the institutions that employ us, are engaging in a social innovation that is part of an overarching change to the fundamental nature of New Zealand society. An ex-British colony, shaped by a 19th Century imperial agenda to ‘civilise the natives’, enforced through a repressive regime, is, in the 21st Century pioneering initiatives and innovations to address that troubled history. This comprises the resurgence of Te Reo (Graham-McLay, 2018) [6]; the Prime Minister, Jacinda Arden, giving her child a Māori name (Guardian, 2018) [7]; the adoption by government of Māori values into annual budgeting (Wellbeing Budget, 2021) [8]; the international acknowledgement of the Haka (the traditional ‘dance’ performed by the All Blacks before international rugby games); tā moko (Māori tattoo) gracing the bodies of many non-Māori, including British musician Robbie Williams; and the incorporation of commitments to Māori people and culture, as articulated in the AUT strategic directions.

All of these positive outcomes have grown from Māori activism and protest, as much as largesse by the dominant culture. They are manifestations of a model of social innovation for, with and by disadvantaged peoples, founded on:

- Empowered communities and strategic leadership

- A social climate open to addressing past inequities

- Strong allies, open to collaboration for social change and social justice

These are key factors for building a better New Zealand, which is succinctly expressed by the Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation as building best practice across business, civil society, policy and academia for a more equitable, inclusive and sustainable world.

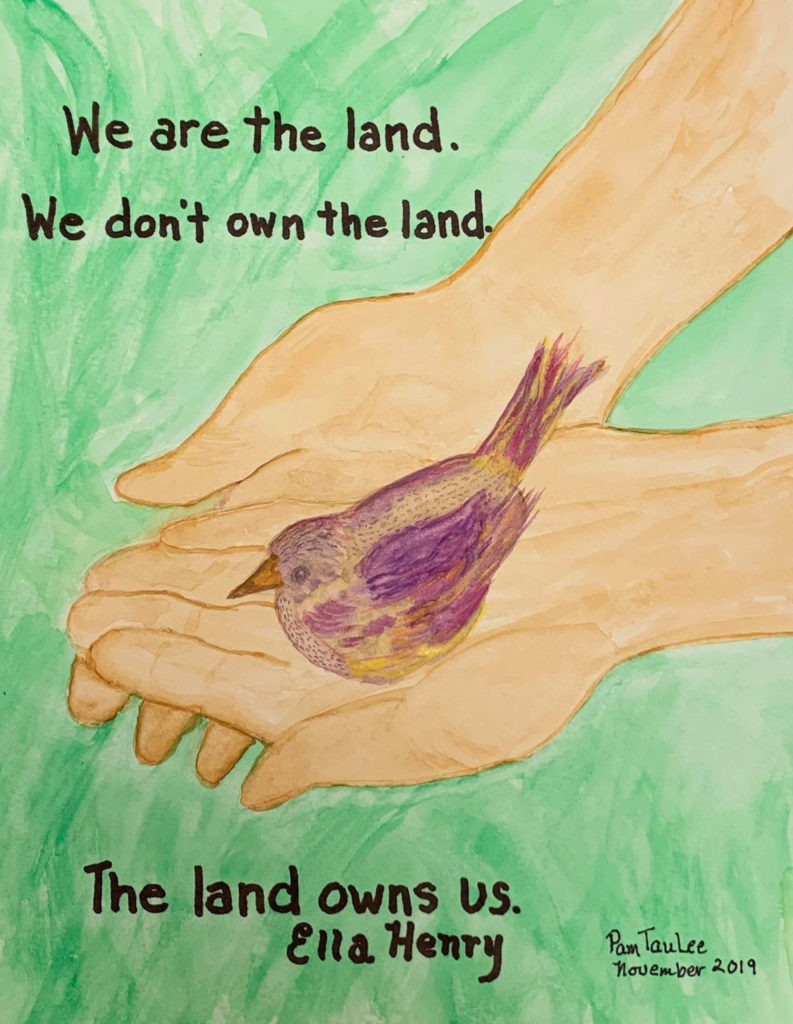

Dr Ella Henry

Ella Henry is a Māori (Indigenous) woman from Aotearoa New Zealand, with tribal affiliations to three tribes from the Far North of the country. She is an Associate Professor in Management, in the Faculty of Business, Auckland University of Technology. Ella’s PhD focussed on Māori entrepreneurship in the screen industry, and her Masters’ on Māori women in leadership. She has also published research on Māori Indigenous development, careers, housing, networking and media.

The Social Innovation Think Tank: Indigenous social innovation

In the fifth episode of The Social Innovation Think Tank, Dr Neil Stott and Professor Paul Tracey discuss ‘Indigenous Social Innovation’. Our guests are Dr Ella Henry from Auckland University of Technology, and Dr Bettina Schneider from First Nations University of Canada; both share their perspectives on Indigenous social innovation.

References

[1] Pue, K., Vandergeest, C., & Breznitz, D. (2015). Toward a theory of social innovation. Innovation Policy Lab White Paper, (2016-01). Retrieved 17th June 2021 from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2701477 [2] Salesa, T. D. (2001). ‘The Power of the Physician’: Doctors and the’Dying Maori’ in Early Colonial New Zealand. Health and History, 3(1), 13-40. [3] Hill, R. S. (2012). Maori urban migration and the assertion of indigeneity in Aotearoa/New Zealand, 1945–1975. Interventions, 14(2), 256-278. [4] Waitangi Tribunal (nd), Ministry of Justice, New Zealand:https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/about-waitangi-tribunal/past-present-future-of-waitangi-tribunal/ [5] MFAT (2018). The Māori Economy. Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade. Retrieved on June 18, 2021 from: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/Trade-agreements/UK-NZ-FTA/The-Maori-Economy_2.pdf [6] Graham-McLay, C. (2018). Māori language once shunned is having a renaissance in New Zealand. New York Times. Retrieved on June 18th 2021 from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/16/world/asia/new-zealand-maori-language.htm [7] Guardian (2018, June 24). Neve Te ArohaNZ MP Jacinda Ardern reveals name of baby daughter. Retrieved June 18 2021 from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jun/24/neve-te-aroha-new-zealand-pm-jacinda-ardern-reveals-name-of-baby-daughter [8] Walker, R. (1990). Ka whaiwhai tonu matau: struggle without end. Penguin Books. Wellbeing Budget. (2021). NZ Budget, Treasury. Retrieved on June 18th 2021 from: https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-05/b21-wellbeing-budget.pdf

Leave a Reply