Indigenous people and the pandemic

Written by Dr Ella Henry, Associate Professor and Director of Māori Advancement, Auckland University of Technology School of Business, Economics and Law – Aotearoa New Zealand; and Associate Research Fellow, Cambridge Centre for Social Innovation.

COVID-19 has impacted on vulnerable populations around the world, particularly Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour [1]. As with other marginalised groups, many Indigenous peoples have worked tirelessly to overcome these and other challenges for their own communities [2].

New Zealand has received accolades for its response to the pandemic. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s epithet to ‘Go hard and go early’ is an example of a national strategy that was embraced by the country, during the first phase of lockdowns and elimination in 2020; but Māori, the Indigenous people of New Zealand, continue to be critical of the government response. For example, Tahana [3] wrote in September 2021 that “most of the country’s newly-declared cases of Covid-19 are Māori; the only death from this Delta outbreak has been a [Māori]; and only about one in four Māori are fully vaccinated – well behind every other group”. Alongside these concerns, Māori have developed their own innovative approaches to protect their communities, as they did after the Christchurch earthquake, opening community centres, offering help and support not just for the Māori community.

On that point, Kenney & Phibbs [4] noted a dearth of Māori representation in national and local emergency management agencies, which meant that Māori community needs’, alongside capacity and capability, were too often over looked. McMeeking & Savage [5] also provide a useful insight into Māori experiences with COVID-19, noting that Māori infection rates have been one example where slightly better social outcomes have been achieved, in terms of infection rates and deaths. They analysed factors that contributed to these positive outcomes, writing, “Māori responses to Covid-19 fall within four broad categories: cultural adaptation, social cohesion and information channels, distributive networks and community protection” (p. 37).

Traditional practices and social cohesion

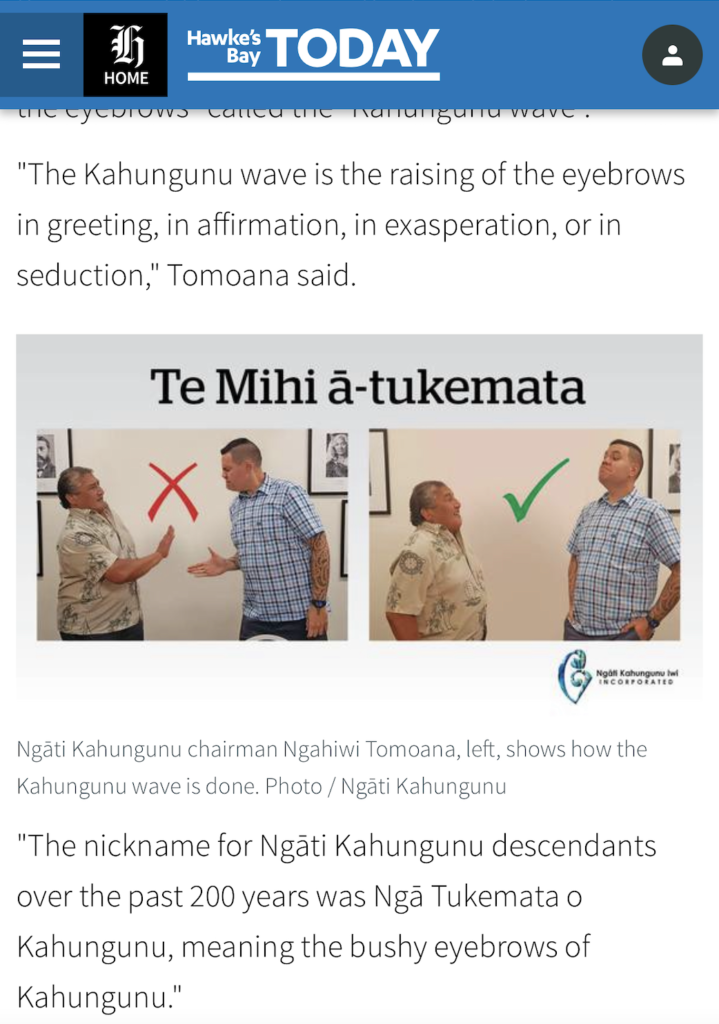

Cultural adaptation involved amending traditional practices during the pandemic. For example, the Māori welcome often involves a hongi, rubbing noses and sharing breath, to cement a relationship founded on friendship and trust. This practice might have been dangerous in the early stages of the pandemic, so one tribe, Ngāti Kahungunu, created a meme entitled the ‘Kahungunu Wave’ (a gesture of the eyebrows rather than the hongi), as a safer alternative. [see Figure 1: Kahungunu Wave].

Social cohesion and information channels refers to the strength of traditional Māori networks, be they tribal, family or community linkages, as more effective channels for information dissemination, rather than mainstream marketing and media strategies. These links are equally important for distribution of resources and support, particularly in isolated rural communities, or when people are reticent to reach out to government agencies, where there is residual antipathy because of historical events, including colonisation, land confiscation and open warfare (Walker, 1990) [6]. [see Figure 2: Te Reo signage].

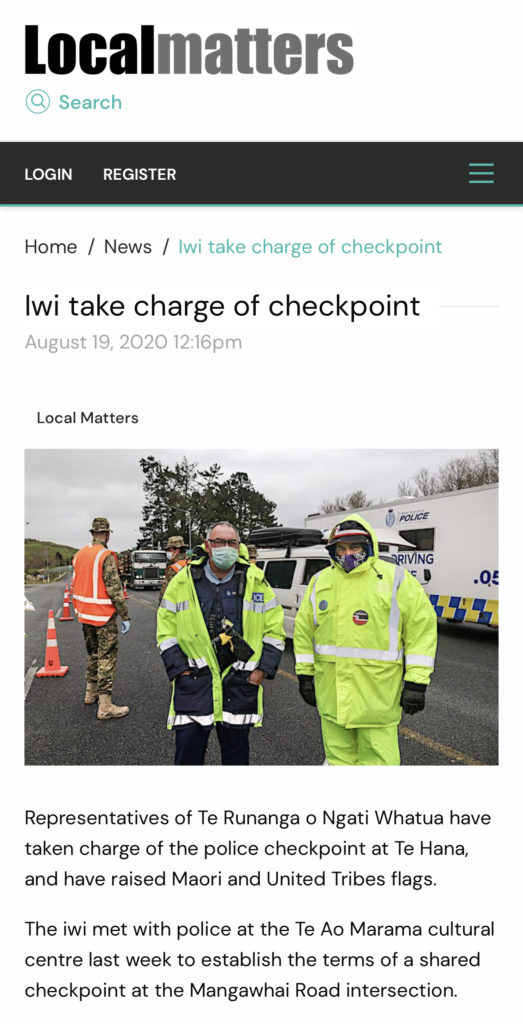

Examples of community protection include roadside checkpoints setup by a number of tribal groups to protect their often poor and isolated communities. This is certainly the case in the Far North, and on the east and west coasts of the North Island. These roadblocks were sanctioned by government, and in some cases supported by the police, but received political and public backlash from those who did not feel that Māori had the right to initiate such strategies. One right-wing politician labelled those manning tribal road-blocks as ‘thugs’ (Dexter, 2021) [7]. One Māori politician from the Far North describes these criticisms as outright racism [8]. [see Figure 3: Iwi roadblock]

McMeeking & Savage conclude that Māori were vulnerable to the worst effects of the virus, often exacerbated by poverty and isolation, but one could argue those same communities were resource-rich when it comes to infrastructure based on cultural values that exemplify community spirit and working collaboratively. They conclude that, “Māori community has all the components of a social movement geared to positive social transformation: organisational infrastructure, financial resources, human talent, deep insight into the needs and aspirations of the community” [9]. [see Figure 4: Tainui Iwi]

Māori and social innovation

Some Māori social innovations arose organically from the ground up; whilst others were initiated from the top down by large Māori organisations working collaboratively. Among these, a collective of Iwi (tribes) setup their own national pandemic-response group, which brought together tribal leadership and Māori health experts to give Māori a stronger voice, and where necessary, to challenge government strategies and policies [10]. This group identified key issues which they believed the government had a responsibility to address, if it took seriously the partnership envisaged in the Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document of the country. Amongst the concerned they raised was:

• the need for the Crown to stop its ‘one size fits all’ model, and to ensure that specific Māori needs are addressed;

• to make systemic and structural changes within the health system that mitigate against existing inequities and institutional racism that underpin many Māori disparities in health;

• for there to be a whole-of-government collaboration with Māori that deals with wider systemic issues such as poverty, housing and wider economic issues that are faced disproportionately by Māori [11].

Taken together, these Maori approaches to health and wellbeing, coming together, collaborating to protect their community and environment, are based on traditional values and ethics that embody physical and spiritual connections to people and place. Those relationships are maintained through cultural practices and language, which have survived despite the ravages of colonial conquest, dispossession of land, language and culture by the dominant state, and the consequent impoverishment that has plagued the Māori population for over a century, and which was reflected in the much higher death rate during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

These values and ethics, amongst many others, shape Māori social innovation: manākitanga (generosity), rangatiratanga (collaborative leadership), and kaitiakitanga (guardianship and stewardship); which in turn strengthen communities of whānau (families), hapū and iwi (tribal groups), leading to improved hauora (health), and wairuatanga (spiritual wellbeing). These concepts are embedded in language and practice (te reo me ngā tikanga) at the community-level, and across Māori entities in terms of strategy and organisational practice. However, for these concepts and practices to flourish, and reach their full potential to enhance Māori wellbeing, they must receive adequate acknowledgment, support and resources from government, as part of its obligations under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which is commemorated on February 6th, Waitangi Day. This is not only a public holiday, but a reminder to Aotearoa New Zealand that we share something unique and distinctive that marks us out from many other Commonwealth nations, which have been bruised by their colonial history. This partnership between coloniser and colonised, Indigenous peoples and settlers, can and should underpin a new and stronger identity moving forward, despite the trauma of a global pandemic. [see Figure 5: Māori communities]

Dr Ella Henry

Ella Henry is a Māori (Indigenous) woman from Aotearoa New Zealand, with tribal affiliations to three tribes from the Far North of the country. She is an Associate Professor in Management, in the Faculty of Business, Auckland University of Technology. Ella’s PhD focussed on Māori entrepreneurship in the screen industry, and her Masters’ on Māori women in leadership. She has also published research on Māori Indigenous development, careers, housing, networking and media.

References

- Curtice & Choo, 2020; Devakumar, Shannon, Bhopal & Abubakar, 2020; Ferrante & Fearnside, 2020; Power, Wilson, Best, Brockie, Bearskin, Millender & Lowe, 2020; Berkowitz, Gao, Michaels & Mujahid, 2021.

- Meneses-Navarro, Freyermuth-Enciso, Pelcastre-Villafuerte, Campos-Navarro, Meléndez-Navarro & Gómez-Flores-Ramos, 2020; Moodie, Ward, Dudgeon, Adams, Altman, Casey, Cripps, Davis, Derry, Eades, Faulkner, Hunt, Klein, McDonnell, Ring, Sutherland & Yap, 2021.

- Tahana, J. (2021, 23 Sept). Government denies it has failed Māori on Covid. NZ Radio New Zealand online. Retrieved from: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/452174/government-denies-it-has-failed-maori-on-covid

- Kenney, C., Phibbs, S. (2015). A Māori love story: Community-led disaster management in response to the Ōtautahi (Christchurch) earthquakes as a framework for action. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 12, 46-55.

- McMeeking, S., Savage, C. (2020). Maori responses to Covid-19. Policy Quarterly, 16(3), 36-41

- Walker, R. (1990). Ka whawhai tonu mātau: struggle without end. Penguin Books

- Dexter, G. (2021, Dec 7). Coronavirus: Northland’s iwi-led checkpoints prompts racism row after David Seymour calls those manning borders ‘thugs’. Newshub online. Retrieved from: https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2021/12/coronavirus-northland-s-iwi-led-checkpoints-prompts-racism-row-after-david-seymour-calls-those-manning-borders-thugs.html

- Witton, 2021

- McMeeking & Savanfe, 2020, p. 40

- Pihama, L., Lipsham, M. (2020). Noho Haumaru: reflecting on Māori approaches to staying safe during Covid-19 in Aotearoa (New Zealand). Journal of Indigenous Social Development, 9(3), 92-101.

- Pihama, & Lipsham, 2020, p. 97

Leave a Reply